A Review of "Biblical Critical Theory"

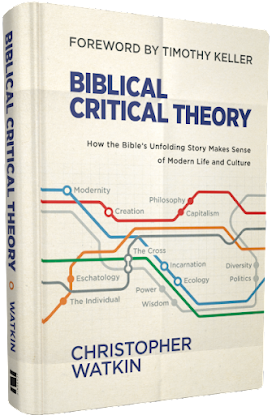

Christopher Watkin’s Biblical Critical Theory was one such book for me. It joins the ranks of Packer’s Knowing God and basically all the C.S. Lewis I’ve ever read as a paradigm-shifting book.

Summary:

The click-baity title aside, this is not really another work dealing with the various Critical Theories stalking the earth these days. Instead, Watkin shows how the storyline of the Bible provides us with a comprehensive cultural theory. He shows how the Bible “diagonalizes” the “reductive heresies” of the bifurcated alternatives offered to us by the modern world. Far from offering a bland porridge of third-way bothisms, Watkin shows how the Bible’s categories transcend our finite categories of “either/or.”

While my overall evaluation of BCT is overwhelmingly positive, I did have a few quibbles with the book's argument. I'll lay these out this week, before concluding with the positive takeaways next week.

First, it was not always clear to me how Watkin got from Biblical text to modern issue. His bridges were occasionally shrouded in the mists of philosophical jargon or obscured by the shrubbery of flowery language. For example, it wasn't obvious to me what the connection was between the Incarnation and Brexit, or between the Abrahamic covenant and the discussion of the sublime and beautiful. These failures may say more about my ignorance as a reader than Watkin's skill as a writer. Still, I did find myself re-reading sections asking, "How did we get from this to that?"

Second, while I think that "diagonalization" is a valid and valuable tool, Watkin, on occasion, could be interpreted by an injudicious reader as presenting modernity's two options as morally equal, particularly when he placed market and state side-by-side. There are surely dangers in both, but I would maintain that the dangers are not morally symmetrical. In less careful hands, the scalpel of diagonalization may do real damage.

Finally (and this is my weakest critique) I do wish that Watkin had tackled some of today's controversial issues more directly. It would have increased the book's value had it dealt directly with current issues like CRT, transgenderism, and the like. While Watkin did brush up against them at times and certainly deals with their underlying premises, I would have loved to hear him discuss these issues candidly. I want to be careful to not ding Watkin for failing to write a different book; I enjoyed this book so much that I would have relished reading his treatment of these issues.

Takeaways for Preaching:

With that said, I want to provide a catalogue of the positives I took away from the book. Rather than offer a full-fledged critique of this book, I would like to show how Watkin’s model should change our preaching.

How so?

It’s one thing to break out the appropriate proof-texts when dealing with particular issues: “We have to be against this because the Bible says so.” Conversation over.

It’s another thing to show how the Bible’s storyline and its worldview transcend, critique, and out-narrate today's cultural narratives. Watkin shows us that the Bible’s message is not only right but more attractive and more compelling than the world’s alternatives. The Biblical prophets model this: they alternate between judgment oracles and salvation oracles. They pull no punches in calling out sin, but they withhold no tool in the rhetorical toolbox in portraying the beauty of restoration and deliverance. We are left thinking, “Even if I don’t believe this, I want it to be true!” Would to God that we could present God’s truth in such a way as to show its beauty, attractiveness, and truth.

The Bible does not merely tell us what’s wrong. It shows us that what is right is infinitely better. It doesn’t just give us the “what.” It also gives us the “why.” It does not merely give us the conclusions, it gives us, embedded in both its larger storyline and individual texts, the reasoning that leads to those conclusions.

We need to show our people from the storyline of the Bible (Creation, Fall, Redemption) why sin runs counter to God’s gloriously good purpose for human flourishing. God’s Law is not an arbitrary rule handed down from on high to squelch human happiness. Rather, it is a gift that harmonizes with God’s created reality, a body of commands that, when followed, leads to our joy, and when ignored, our destruction.

2. It helps us preach relevantly.

The Bible is the most relevant text in the world. Watkin shows how the Bible’s storyline interacts with, critiques, and out-narrates the great thinkers of both past and present. the Bible is not to be sealed off from cultural critique or philosophical discussion. It is not relegated to the cloistered corridors the church or the academy.

Now, the truth is, few people in our pews are reading philosophers or critical theorists. But we are absorbing their ideas nonetheless through popular media and cultural liturgies.

In preaching, we need to put to work the tools of diagonilization and cultural analysis that Watkin models so admirably. In expounding the text, we need open eyes to both the glimmering realities of the Word before us and the ephemeral beliefs of the world around us. We need to, with Paul, be able to both expose the folly of Areopagus and show how the truth of God fulfills the deepest longings of our hearts.

Relevant preaching is not simply preaching that gives readily-applicable tips and steps that lead to improved living; it is not preaching that is trendy and hip. Rather, relevant preaching shows how God’s truth is big-T truth that helps us see all other truths in one coherent whole. It’s Lewis's sunrise we can see and the sunrise by which we see everything else. So show how the Bible helps us think rightly about technology, capitalism, war, marriage, sex, entertainment, creation, ecology, ethics, worship, and architecture. It’s not that there’s a Bible verse for all these topics; it’s that there’s a framework for understanding them.

3. It helps us preach evenly.

In today’s tribalistic age, it is a dangerously alluring temptation to wield the Bible as an axe in the partisan fights of our online battlefields. To be sure, the Bible does indeed come down firmly and unambiguously against many idols of our age: abortion, gay marriage, transgenderism, statism, greed, materialism, racism, and the like. But if we’re not careful, we’ll assume that the right’s agreement with the Bible on a few clear-cut issues signals the Bible’s agreement with the right’s beliefs on everything else. The reality is that the Bible’s storyline warns against both statism and materialism, against both the excesses of utopian socialism and unrestrained greed of the godless market. It warns against both the raw individualism of the right and the conformist communitarianism of the left. It denounces both sexual perversion and racial discrimination.

In recognizing these realities, pastors and preachers can declare the Bible in such a way as to make application to all in our world today. We can be quite good at calling out the sins that are already frowned upon in our neck of the woods. In a conservative climate, it takes little courage to call out transgenderism (and we should call it out!), but if we’re silent on racism are we truly preaching against the idols of our time and place? Likewise, in a progressive climate, one would presumably face little anger if he preached against racism and worker exploitation, but would face blowback for calling out abortion and homosexuality. The Bible’s storyline critiques both, and so should we.

4. It shows us how to preach redemptively.

If you’re an expositor like me, you spend much of your week digging into your text’s literary and historical context. You nail down what it meant there and then. You then seek to bring it to bear on the lives of your people here and now.

5. It shows us how to preach beautifully.

It would be a mistake to assume that, because Watkin is an academic expert in French Critical Theorists, that his work is a stale tome written in staid prose. Watkin writes with a warmth and beauty that conveys the warmth and beauty he admires in the Bible’s story. He naturally weaves vivd metaphors into his paragraphs. He states timeless truths in thought-provoking ways.

I’ll be honest, my preaching tends to be pretty cut and dry. I like structure, logic, and order. And while there’s a certain beauty in a logical outline, we expositors often lack the vividness that marks the Hebrew prophets, the turn-of-phrase that is the paint of the wise man’s artistry in Proverbs, the pathos of the Psalmist’s lament, and the down-to-earth story-telling of our Lord. Even Paul, often regarded as a cold logician, employs many a rhetorical device in his letters, including surprising and creative quotations of Scripture, paronomasia, hyperbole and on and on.

Since reading Watkin's book, I’ve been making a concerted effort to craft the language of my sermons, not for a “I hope the people are impressed” response, but for a “I hope they can see the beauty of God’s truth.” Just as the painter conveys the beauty of God’s outside book with artistic technique, so the preacher should convey the beauty of God’s inside book with beautiful words.

Comments

Post a Comment